🌷 “The first phase of the Reformation was Amyraldian in the sense that the churches professed a strong view of divine predestination while also affirming a universal perspective on the extent of the atonement.”

St. Augustine, Luther, Calvin, & Jonathan Edwards never held to “Limited Atonement.” The Bible does not support limited atonement: 1 Jn 2:2; 4:14; Jn 1:9,29; 3:17; 4:42; 12:32; Ac 2:21; Ro 5:6; 1Ti 2:3-4,6; Titus 2:11; 2Cor 5:19; 2Pe 3:9.

The Bible is the final authority.

— 𝕊𝕖𝕧𝕖𝕟𝕊𝕙𝕖𝕡𝕙𝕖𝕣𝕕 ♱ (@SevenShepherd) October 2, 2023

"and he himself is the atoning sacrifice for our sins, and not only for our sins but also for the whole world."

— 1 John 2:2 NET#Jesus #God #Bible #Christian #Atonement #Unlimited pic.twitter.com/uJmWW3h1VJ

- Amyraldism Is Moderate Calvinism

- Distinctives of Amyraldism

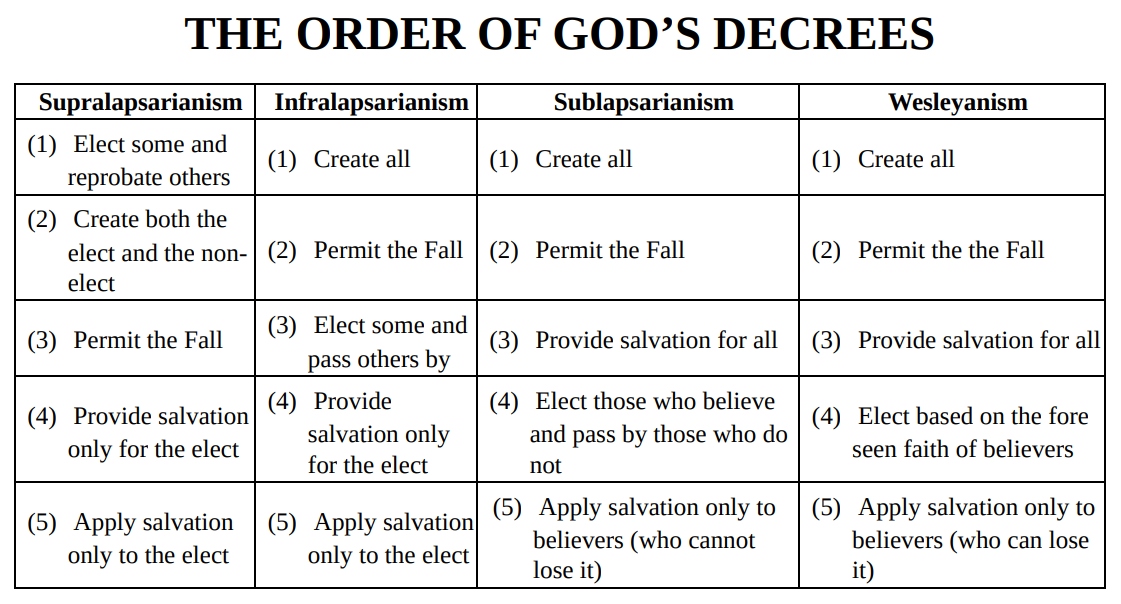

- The Order Of Decrees

- Ordo Salutis

- Rejections of Limited Atonement

- Scholars & Theologians

- Sources & Citations

the first phase of the Reformation was Amyraldian — Dr. Michael F. Bird (Ph.D., University of Queensland), Evangelical Theology, 4.4 The Death of Jesus, 4.4.3.3 Amyraldian View. p. 486.

Amyraldism, Amyraldianism, Moderate Calvinism, or “four-point” Calvinism is a modified form of Calvinism which rejects limited atonement and replaces it with unlimited atonement. It is one of several hypothetical universalist systems.

II. Distinctives of Amyraldism

The following information was constructed from gotquestions.org.

T—Total Depravity – Man, in his fallen state, is completely incapable of doing any good that is acceptable to God.

U—Unconditional Election – As a result of man’s total depravity, he is unable (and unwilling) to come to God for salvation. Therefore, God must sovereignly choose those who will be saved. His decision to elect individuals for salvation is unconditional. It is not based on anything that man is or does but solely on God’s grace.

L—Unlimited Atonement – The particular point that Amyraldism denies is the third point, limited atonement. Amyraldism replaces it with unlimited atonement, or the concept of “hypothetical universalism,” which asserts that Christ died for the sins of all people, not just the elect. Amyraldism preserves the doctrine of unconditional election even while teaching unlimited atonement this way: because God knew that not all would respond in faith to Christ’s atonement (due to man’s total depravity), He elected some to whom He would impart saving faith.

I—Irresistible Grace – The Holy Spirit applies the finished work of salvation to the elect by irresistibly drawing them to faith and repentance. This saving call of the Holy Spirit cannot be resisted and is referred to as an efficacious call.

P—Perseverance of the Saints – Those whom God has elected, atoned for, and efficaciously called are preserved in faith until the last day. They will never fall away because God has secured them with the seal of the Holy Spirit. The saints persevere because God preserves them.

3.1 As delineated by Dr. Bruce Demarest

In sum, regarding the question, For whom did Christ die? we find biblical warrant for dividing the question into God’s purpose regarding the provision of the Atonement and his purpose concerning the application thereof. Scripture leads us to conclude that God loves all people he created and that Christ died to provide salvation for all. The provision side of the Atonement is part of the general will of God that must be preached to all. But beyond this, the Father loves the “sheep” with a special love,117 and in the divine will the Spirit applies the benefits of Christ’s death to the “sheep,” or the elect. The application side of the Atonement is part of the special will of God shared with those who come to faith. This conclusion—that Christ died to make atonement for all to the end that its benefits would be applied to the elect—coheres with the perspective of Sublapsarian Calvinism [Moderate Calvinism]. It differs from the Supralapsarian [Hyper-Calvinism] and Infralapsarian schemes [Scholastic Calvinism], which teach that Christ died to make provision only for the sins of the elect. And it differs from the Arminian scheme [Wesleyan] of decrees, which states that God willed the application of the Atonement to all, but that the divine purpose was frustrated by human resistance. A.H. Strong reflected the biblical perspective when he wrote, “Not the atonement therefore is limited, but the application through the work of the Holy Spirit.”118

Thomas J. Nettles designates this development a modification of the limited Atonement hypothesis.119 Millard J. Erickson, reflecting on classical formulations of the ordo salutis, describes the position as a form of the unlimited or universal Atonement thesis.120 The view presented may be neither, as it divides the question into the divine intention concerning the provision of the cross, which is universal, and his intention concerning the application thereof, which is particular. The position outlined is not Arminianism (as some allege) but a viewpoint close to that of Calvin himself—a position that was narrowed by later, scholastic Calvinism. Our perspective, moreover, offers greater specificity than the dictum frequently articulated in evangelical circles: “The Atonement is sufficient for all but efficient for the elect.” Rather, it affirms that by divine intention Christ’s suffering and death are universal in its provision and particular in its application.

A. Realize That Christ Died for You

The multiple purposes of Christ’s death on the cross can be represented by three concentric circles. The largest circle represents the entire world for whom the Savior died as the adequate provision for sins (1 Tim 4:10; 1 John 2:2; 4:14). The middle circle delineates the sum of all believers, i.e., the church (John 10:11, 15; Acts 20:28; Rom 8:32; Gal 1:4; Eph 5:2), to whom Christ’s saving provisions were actually applied. And the innermost circle represents the individual believer for whom Christ made atonement (Gal 2:20b). That Christ died for me and for you individually and personally is made clear by Paul’s words in the preceding text: “the Son of God . . . loved me [me] and gave himself for me [hyper emou].” It is highly significant that in describing the true Gospel and its ministry Paul used the first-person, singular pronoun twenty-eight times in this second chapter of Galatians.

How blessed it is to realize that Christ took my place on the cross and was forsaken of God for me. For my sins he bore in his body the penalty required by a holy and just God. …

— Dr. Bruce Demarest (Ph.D., University of Manchester), The Cross and Salvation, Chapter Four, The Doctrine of Atonement. pp. 193-194.

3.2 As delineated by Dr. Jeff Fisher

The following is a chart from the book Unlimited Atonement: Amyraldism and Reformed Theology on page 148.

| Supralapsarian (Before the Fall) |

Infralapsarian (After the Fall) |

Amyraldianism |

|---|---|---|

| Elect some and condemn others | Create free humans | Create free humans |

| Create the elect and the reprobate | Permit the fall | Permit the fall |

| Permit the fall | Elect some and leave others condemned | Provide salvation for all through Christ’s death |

| Provide salvation for the elect through Christ’s death | Provide salvation for the elect through Christ’s death | Elect some to receive effectual grace |

3.3 As delineated by Dr. Norman Geisler

The term supralapsarian is from the Latin supra (above) and lapsus (fall), meaning that God’s decree of election (predestination) is considered by supralapsarians to be above, or logically prior to, His decree to permit the Fall. Since infra means “below,” the infralapsarians consider God’s decree of election to be beneath, or logically after, His decree to permit the Fall. The sublapsarians (Amyraldians) 9 are similar to the infralapsarians, except they place God’s order to provide salvation before His order to elect (see Chafer, ST, 2.105). Wesleyans adhere to the same basic order as infralapsarians, except they hold that God’s election is based on His foreknowledge rather than simply in accord with it. Hence, for Wesleyans (Arminians), God’s decree is conditional instead of unconditional (which is maintained by the three Calvinistic views).

Supralapsarians are hypter-Calvinists, being double-predestinarians. 10 Infralapsarians are strong Calvinists but are not double-predestinarians. Sublapsarians (Amyraldians) are moderate Calvinists, holding to unlimited atonement. Again, Wesleyans are Arminians, insisting that election is conditional, not unconditional. Wesleyans also do not believe in eternal security, 11 while adherents to the other views do.

— Dr. Norman Geisler (Ph.D., Philosophy, Pennsylvania; M.A., Theology, Wheaton), Systematic Theology, Volume Three, Sin Salvation. p. 179?

–

Moderate Calvinists and moderate Arminians, who represent the vast majority of Christendom, have much in common against the extremes in the opposing two views. Indeed, John Wesley himself (a moderate Arminian) said he was only a “hair’s breadth from Calvin.” And as is later demonstrated in appendix 2, Calvin himself rejected some things held in later extreme Calvinism (e.g., limited atonement). — Dr. Norman Geisler (Ph.D., Philosophy, Pennsylvania; M.A., Theology, Wheaton)

3.4 As delineated by Dr. R.C. Sproul

There is a simpler chart provided by R.C. Sproul, who simplifies the difference between supralapsarianism and infralapsarianism into an asymmetrical and symmetrical view. It would seem that Hyper-Calvinism (supralapsarianism) is rightly rejected by all sides of the debate about God’s decrees, because of the egregious violence it does to God’s character in insinuating that He could possibly coerce sin.

| Scholastic Calvinism (Infra.) | Hyper-Calvinism (Supra.) |

|---|---|

| Positive-negative | Positive-positive |

| Asymmetrical view | Symmetrical view |

| Unequal ultimacy | Equal ultimacy |

| God passes over the reprobate | God works unbelief in the hearts of the reprobate. |

The dreadful error of hyper-Calvinism is that it involves God in coercing sin. This does radical violence to the integrity of God’s character. — Dr. R. C. Sproul (Ph.D., Whitefield), “Chosen by God,” Ch. 7. Sproul was a devout 5-point Scholastic Calvinist

… there is such a thing as hyper-calvinism which is not historic calvinism it’s always been a tiny group who have twisted the bible by their unbiblical logic. Dr. John Piper (D.Theol., Munich), a devout 5-point Scholastic Calvinist

Ordo salutis is a latin phrase for “The Order of Salvation” and was first coined by Lutheran theologians Franz Buddeus and Jacob Carpov in the first half of the eighteenth century. This article is not an endorsement.

Since the only real difference between Calvinism & Moderate Calvinism is the extent of the atonement and slight alteration to the order of decrees, the ordo salutis should be identical to Scholastic Calvinism. Ordo salutis provided by Dr. Bruce Demarest.1

- Calling

- The general call to trust Christ is issued through the widespread offer of the Gospel. By means of this general call God sovereignly issues a special calling to the elect. The Spirit facilitates sinners’ response to the Gospel by enlightening their minds, liberating their wills, and inclining their affections Godward.

- Regeneration

- Without any human assistance the third person of the Trinity creates new spiritual life, including God-honoring dispositions, affections, and habits.

- Faith

- Having been granted new spiritual life, the elect believe the truths of the Gospel and trust Jesus Christ as Savior. Faith is viewed as a gift and enablement of God, indeed as a consequence of new spiritual birth.

- Repentance

- Here believers grieve for sins committed and deliberately turn from all known disobedience. This response likewise is a divine enablement.

- Justification

- On the basis of Christ’s completed work, the Father reckons to believers the righteousness of his Son, remits sins, and admits the same to the divine favor. Justification is the legal declaration of believing sinners’ right standing with God.

- Sanctification

- The Holy Spirit works in justified believers the will and the power progressively to renounce sin and to advance in spiritual maturity and Christlikeness. By the process of sanctification God makes believers experientially holy.

- Preservation and perseverance

- The God who has chosen, regenerated, justified, and sealed believers with his Spirit preserves them by his faithfulness and power to the very end. True believers persevere by virtue of the divine preservation.

- Glorification

- God will complete the redemption of the saints when the latter behold Christ at his second advent and are transformed into his likeness.

V. Rejections of Limited Atonement

5.1 Early Church Fathers Who Rejected Limited Atonement

| Early Church Fathers | |

|---|---|

| 150 – 220 | Clement of Alexandria Rejected Limited Atonement |

| 260 – 340 | Eusebius Rejected Limited Atonement |

| 293 – 373 | Athanasius Rejected Limited Atonement |

| 315 – 386 | Cyril of Jerusalem Rejected Limited Atonement |

| 324 – 389 | Gregory of Nazianzen Rejected Limited Atonement |

| 330 – 379 | Basil Rejected Limited Atonement |

| 340 – 407 | Ambrose Rejected Limited Atonement |

| 354 – 430 | St. Augustine of Hippo Rejected Limited Atonement |

| 376 – 444 | Cyril of Alexandria Rejected Limited Atonement |

5.2 Reformers Reject Limited Atonement

| Historical Scholars | |

| 1483 – 1546 | Martin Luther Rejected Limited Atonement ▫️ On the Bondage of the Will |

| 1509 – 1564 | John Calvin Rejected Limited Atonement ▫️ Institutes of the Christian Religion |

5.3 Dr. Ron Rhodes Defends Unlimited Atonement & Amyraldism

In an article titled “The Extent of the Atonement,” Dr. Ron Rhodes picks apart limited atonement.

My position is known in theological circles as “4-point Calvinism. … As a 4-point Calvinist, I hold to all the above [TULIP] except limited atonement [‘L’]. — Dr. Ron Rhodes (Th.D., Dallas Theological Seminary), The Extent of the Atonement.

-

5.3.1 Dr. Walter Martin Quoted

Walter Martin, founder of the Christian Research Institute, observes: “John the Apostle tells us that Christ gave His life as a propitiation for our sin (i.e., the elect), though not for ours only but for the sins of the whole world (1 John 2:2)….[People] cannot evade John’s usage of ‘whole’ (Greek: holos). In the same context the apostle quite cogently points out that ‘the whole (holos) world lies in wickedness’ or, more properly, ‘in the lap of the wicked one’ (1 John 5:19, literal translation). If we assume that ‘whole’ applies only to the chosen or elect of God, then the ‘whole world does not ‘lie in the lap of the wicked one.’ This, of course, all reject.”

5.4 Dr. John C. Lennox Dispatches Limited Atonement

Dr. John C. Lennox, while not an Amyraldian himself and choosing to go systemless, also contributes many vital points in his book “Determined to Believe?” if you want something more in-depth and expansive.

All of this invalidates the L of TULIP – “limited atonement” – the view that Christ did not actually die for all but only for the “elect”. In fact, not only Luther but many of the other reformers, including Calvin, did not subscribe to limited atonement… this view of the atonement was not even introduced until the second or third generation of Reformers… — Dr. John C. Lennox (PhD, University of Cambridge; DPhil, Emeritus Professor of Mathematics at the University of Oxford; DSc, Cardiff University), Determined to Believe? p. 179.

5.5 Dr. Carson’s Multiple-Intentions

Read “The Difficult Doctrine of the Love of God” pp. 73-78 (Amyraldian view, 73-74). Or check out this article about it.

While Carson “lumps together” the Arminian and the Amyraldian in this book, he is actually arguing for a ‘multiple-intentions’ view of the atonement, such as is advocated by Amyraldians (Moderate Calvinists), which is one of several hypothetical universalist systems.

B. The Love of God and the Intent of the Atonement

Here I wish to see if the approaches we have been following with respect to the love of God may shed some light on another area connected with the sovereignty of God—the purpose of the Atonement.

The label “limited atonement” is singularly unfortunate for two reasons. First, it is a defensive, restrictive expression: here is atonement, and then someone wants to limit it. The notion of limiting something as glorious as the Atonement is intrinsically offensive. Second, even when inspected more coolly, “limited atonement” is objectively misleading. Every view of the Atonement “limits” it in some way, save for the view of the unqualified universalist. For example, the Arminian limits the Atonement by regarding it as merely potential for everyone; the Calvinist regards the Atonement as definite and effective (i.e., those for whom Christ died will certainly be saved), but limits this effectiveness to the elect; the Amyraldian limits the Atonement in much the same way as the Arminian, even though the undergirding structures are different.

It may be less prejudicial, therefore, to distinguish general atonement and definite atonement, rather than unlimited atonement and limited atonement. The Arminian (and the Amyraldian, whom I shall lump together for the sake of this discussion) holds that the Atonement is general, i.e., sufficient for all, available to all, on condition of faith; the Calvinist holds that the Atonement is definite, i.e., intended by God to be effective for the elect.

At least part of the argument in favor of definite atonement runs as follows. Let us grant, for the sake of argument, the truth of election.1 That is one point where this discussion intersects with what was said in the third chapter about God’s sovereignty and his electing love. In that case the question may be framed in this way: When God sent his Son to the cross, did he think of the effect of the cross with respect to his elect differently from the way he thought of the effect of the cross with respect to all others? If one answers negatively, it is very difficult to see that one is really holding to a doctrine of election at all; if one answers positively, then one has veered toward some notion of definite atonement. The definiteness of the Atonement turns rather more on God’s intent in Christ’s cross work than in the mere extent of its significance.

But the issue is not merely one of logic dependent on election. Those who defend definite atonement cite texts. Jesus will save his people from their sins (Matt. 1:21)—not everyone. Christ gave himself “for us,” i.e., for us the people of the new covenant (Tit. 2:14), “to redeem us from all wickedness and to purify for himself a people that are his very own, eager to do what is good.” Moreover, in his death Christ did not merely make adequate provision for the elect, but he actually achieved the desired result (Rom. 5:6-10; Eph. 2:15-16). The Son of Man came to give his life a ransom “for many” (Matt. 20:28; Mark 10:45; cf. Isa. 53:10-12). Christ “loved the church and gave himself up for her” (Eph. 5:25).

— Dr. D. A. Carson (Ph.D., University of Cambridge) “The Difficult Doctrine of the Love of God,” B. The Love of God and the Intent of the Atonement. Amyraldian view, pp. 73-74.

–

Surely it is best not to introduce disjunctions where God himself has not introduced them. If one holds that the Atonement is sufficient for all and effective for the elect, then both sets of texts and concerns are accommodated. As far as I can see, a text such as 1 John 2:2 states something about the potential breadth of the Atonement. As I understand the historical context… It was not for our sins only, but also for the sins of the whole world. The context, then, understands this to mean something like “potentially for all without distinction” rather than “effectively for all without exception”—for in the latter case all without exception must surely be saved, and John does not suppose that that will take place.

— Dr. D. A. Carson (Ph.D., University of Cambridge) “The Difficult Doctrine of the Love of God,” B. The Love of God and the Intent of the Atonement. p. 76.

–

I argue, then, that both Arminians and Calvinists should rightly affirm that Christ died for all, in the sense that Christ’s death was sufficient for all and that Scripture portrays God as inviting, commanding, and desiring the salvation of all, out of love(in the third sense developed in the first chapter). Further, all Christians ought also to confess that, in a slightly different sense, Christ Jesus, in the intent of God, died effectively for the elect alone, in line with the way the Bible speaks of God’s special selecting love for the elect (in the fourth sense developed in the first chapter).

— Dr. D. A. Carson (Ph.D., University of Cambridge) “The Difficult Doctrine of the Love of God,” B. The Love of God and the Intent of the Atonement. p. 77.

5.6 Dr. Michael F. Bird’s Stance

As will be clear, I stand in the Anglican tradition, which holds to the efficacy of Christs death for the elect combined with a universal atonement and a universal offer of the gospel.

— Dr. Michael F. Bird (Ph.D., University of Queensland), Evangelical Theology, 4.4 The Death of Jesus, 4.4.3 The Extent of the Atonement. p. 476.

–

Given these failings, I think that D. B. Knox was right to call limited atonement “a textless doctrine” since it lacks biblical justification, and such a state is “a fatal defect for any doctrine for which a place in Reformed theology is sought.”

— Dr. Michael F. Bird (Ph.D., University of Queensland), Evangelical Theology, 4.4 The Death of Jesus, 4.4.3.1 Limited Atonement View. p. 481.

–

However, the first phase of the Reformation was Amyraldian in the sense that the churches professed a strong view of divine predestination while also affirming a universal perspective on the extent of the atonement. There is mention of election but no support for limited atonement in the First Helvetic Confession (1536), the Scots Confession (1560), or the Belgic Confession (1561). Lutherans and Anglicans both confess divine predestination while simultaneously affirming a universal atonement and the universal offer of the gospel. 146 On the Anglican side, D. B. Knox, a much-neglected Australian Anglican theologian, stands in this tradition of Anglican Calvinism with a universal view of the atonement.147 For Knox, the work of Christ extends uniformly to the whole of humanity, and this is clear when based around certain theological tenets.

— Dr. Michael F. Bird (Ph.D., University of Queensland), Evangelical Theology, 4.4 The Death of Jesus, 4.4.3.3 Amyraldian View. p. 486.

–

I suspect that the Reformed view can be stretched to accept a universal dimension to the atonement. Let us consider what John Owen said, that Jesus’s death has “infinite worth, value, and dignity” and is “sufficient in itself’ to save all persons without exception. Jesus’s death is infinitely sufficient for universal evangelism even “if there were a thousand worlds.”151 Owen, Death of Death, 295-98.

— Dr. Michael F. Bird (Ph.D., University of Queensland), Evangelical Theology, 4.4 The Death of Jesus, 4.4.3.3 Amyraldian View. p. 488.

5.7 Dr. Robert Letham’s Description

Dr. Letham is not an Amyraldian, as far as I can tell he is a scholasitc or orthodox 5-point Calvinist, but he does describe the moderate Calvinist without bias.

14.1.6 Amyraldianism

Moïse Amyraut (1596–1664) held that Christ died on the cross for all people on condition of their faith. However, God the Father elected some to salvation. In turn, the Spirit grants repentance and faith to the elect. As Reymond points out, for Amyraldianism, “the actual execution of the divine discrimination comes not at the point of Christ’s redemptive accomplishment but at the point of the Spirit’s redemptive application.”114 Essentially, Amyraldianism sought to maintain the particularity of election and the application of redemption by the Spirit, while also having a universal atonement. For this reason, Warfield classes it as inconsistent Calvinism.115 Unlike Arminianism, its doctrine of election was not based on God’s foreknowledge of the human response to the gospel. However, its view of the efficacy of Christ’s work was split—he died for all but intercedes for the elect. It appears to drive a wedge between the decree of election, the atonement, and the particularity of application.

14.1.7 Hypothetical Universalism

Some English theologians proposed a slightly different argument than Amyraut.116 Again, the point of disagreement lay more on the intent of the atonement than on election and reprobation. Edmund Calamy (1600–1666), a member of the Westminster Assembly, held that Christ died absolutely for the elect and conditionally for the reprobate, in case they believe. In this context, Calamy preserved the congruence in the works of the Trinity and avoided a split between the atonement and the intercession of Christ.117 Calamy distinguished his position from Arminianism. Arminians say Christ paid a price placing all in an equal state of salvation. Calamy insisted his views “doth neither intrude upon either [the] doctrine of speciall election or speciall grace.” He argued that Arminianism asserted that Christ simply suffered; all people are placed in a potentially salvable situation, so that any who believe will be saved. In contrast, he believed Christ’s death saves his elect and grants a conditional possibility of salvation to the rest.118 In distinction from Amyraut, Calamy held that the atonement is efficacious for the elect. Calamy’s views were not seen as posing a major threat to the Reformed consensus.

This general position is evidenced in John Davenant (1576–1641), a member of the influential British delegation to Dort. From the premise of the need for universal gospel preaching to be grounded on a coterminous provision, he taught that the death of Christ was the basis for the salvation of all people everywhere. The call to faith, given indiscriminately, presupposes that the death or merit of Christ is applicable to all who are promised the benefit on condition of faith. Therefore, the scope and intent of the atonement is universal. Christ paid the penalty for the whole human race, grounded on an evangelical covenant in which he promises everlasting salvation to all on condition of faith in Christ. This sufficiency is ordained by God in the evangelical covenant but is overshadowed by another decree whereby God determined salvation for the elect. No actual reconciliation or salvation comes before a person believes. In this, God makes available or withholds the means of application of salvation to nations or individuals, according to his will. Only the elect receive saving faith. This decree of election, differentiating between elect and reprobate, conflicts with God’s decision that Christ atone for each and every person by his death. God decides first one thing, then another.119

— Dr. Robert Letham (Ph.D., Aberdeen), “Systematic Theology,” 14. Election and the Counsel of Redemption.

The contemporary scholars listed below hold to moderate forms of Calvinism that uphold unlimited atonement or multiple-intentions view of atonement, which is one of several hypothetical universalist systems.

| Early Church Fathers | |

| 354 – 430 | St. Augustine of Hippo Rejected Limited Atonement ▫️ De Doctrina Christiana (On Christian Doctrine) ▫️ De civitate Dei (The City of God, consisting of 22 books) |

| Historical Scholars | |

| 1487 – 1555 | Hugh Latimer |

| 1488 – 1569 | Myles Coverdale |

| 1489 – 1556 | Thomas Cranmer |

| 1509 – 1564 | John Calvin Rejected Limited Atonement ▫️ Institutes of the Christian Religion |

| 1587 – 1628 | John Preston |

| 1594 – 1670 | Jean Daillé |

| 1596 – 1664 | Moïse Amyraut ▫️ Traiti de la Predestination et de ses principales dependances (1634) (Treatise on Predestination) ▫️ Eschantillon de la doctrine de Calvin touchant la predestination (1636) |

| 1600 – 1656 | Richard Vines |

| 1615 – 1691 | Richard Baxter ▫️ Various Writings |

| 1625 – 1699 | William Bates |

| 1627 – 1673 | George Swinnock |

| 1628 – 1680 | Stephen Charnock |

| 1628 – 1688 | John Bunyan ▫️ The Pilgrim’s Progress |

| 1630 – 1705 | John Howe |

| 1671 – 1732 | Edmund Calamy |

| 1703 – 1758 | Jonathan Edwards (Pres. of Princeton) Hypothetical Universalist “The greatest theological mind the New World ever produced.” ▫️ The Works of Jonathan Edwards, Perry Miller. |

| 1718 – 1747 | David Brainerd |

| 1754 – 1815 | Andrew Fuller |

| 1779 – 1853 | Ralph Wardlaw |

| 1780 – 1847 | Thomas Chalmers |

| 1816 – 1900 | J.C. Ryle |

| 1899 – 1981 | David Martyn Lloyd-Jones |

| 1899 – 1993 | Norman F. Douty Did Christ Die Only for the Elect: A Treatise on the Extent of Christ’s Atonement |

| Contemporary Scholars | |

| 1928 – 1989 | Dr. Walter Martin (Ph.D., California Coast) ▫️ Essential Christianity |

| 1932 – 2019 | Dr. Norman Geisler (Ph.D., Philosophy, Pennsylvania; M.A., Theology, Wheaton) ▫️ Systematic Theology, Volume Three, Sin Salvation. |

| 1932 – Present | Millard J. Erickson (Ph.D., Northwestern) |

| 1935 – 2021 | Dr. Bruce Demarest (Ph.D., Manchester) ▫️ The Cross and Salvation |

| 1946 – Present | Dr. D. A. Carson (Ph.D., University of Cambridge) ▫️ The Difficult Doctrine of the Love of God ▫️ Biblical Theology Study Bible ▫️ On Atonement |

| 1953 – Present | Bruce A. Ware (Ph.D., Fuller Theological Seminary) |

| 1959? – Present | Dr. Ron Rhodes (Th.D., Dallas Theological Seminary) ▫️ The Extent of the Atonement |

| 1961 – Present | Dr. Frank Turek (D.Min., Southern Evangelical Seminary) |

| 1974 – Present | Dr. Michael F. Bird (Ph.D., University of Queensland) ▫️ Unlimited Atonement: Amyraldism and Reformed Theology ▫️ Evangelical Theology |

1 Dr. Bruce Demarest (Ph.D., University of Manchester) was senior professor of spiritual formation at Denver Seminary, where he taught since 1975, and a member of the Evangelical Theological Society, Theological Thinkers and Cultural Group, and Spiritual Formation Forum. “The Cross and Salvation: The Doctrine of Salvation (Foundations of Evangelical Theology).” pp. 36-44.