⛏️ “For many are called, but few are chosen.” — Jesus

This is a compilation of quotations and excerpts pertaining to the doctrine of election from the most solid sources. Keep in mind that we’re justified by faith only (Eph 2:8-9; Rom 3:28), not by our understanding of predestination and election.

16 For many are called, but few are chosen.” — Jesus in Matthew 22:14 (cf. Acts 13:48,2:23; Mt 22:14; Eph 1:4,11; Jn 15:16,18-19; Jn 6:44,65; Ro 8:29-30; 9:11-16; 1Pe 1:2; 2 Pe 1:10; Re 13:8,17:8; Lk 24:45+1Cor 2:14; Jn 17:9, and Ro 10:9+1Cor 12:3+Lk 6:46)

- ⭐ Views held or considering

- 🟦 Acceptable / Noteworthy Stances

- 🟩 Scientist Theologians

- 🟥 Unacceptable Stances

- Unconditional Single Election (Foreordination)

- 1.1 Moderately Reformed (Inclination)

- 1.1.1 5-Point Scholastic Calvinist

- 1.1.1.1 Dr. Packer (Oxford)

- 1.1.1.2 Dr. Grudem (Cambridge)

- 1.1.1.3 Dr. Wallace (Dallas)

- 1.1.2 Amyraldian (4-Point Calvinist)

- 1.1.2.1 Dr. Demarest (Manchester)

- 1.1.2.2 Dr. Bird (Queensland)

- 1.1.1 5-Point Scholastic Calvinist

- 1.2 Moderately Reformed (Compatibilism)

- 1.2.1 Amyraldian / More Moderate

- 1.2.1.1 ⭐ Dr. Ross (Toronto)

- 1.2.1.2 ⭐ Dr. Carson (Cambridge)

- 1.2.1.2.1 Men As Responsible

- 1.2.1.2.2 God As Sovereign

- 1.2.1.3 Dr. Martin (CCU)

- 1.2.1.4 Dr. Rhodes (Dallas)

- 1.2.1.5 Dr. Geisler (Loyola)

- 1.2.1 Amyraldian / More Moderate

- 1.1 Moderately Reformed (Inclination)

- Conditional Election (Foreknowledge)

- 2.1 Classical Arminianism (Libertarian)

- 2.1.1 Dr. Polkinghorne (Cambridge)

- 2.1.2 Dr. Oden (Yale)

- 2.2 Wesleyan-Arminian (Molinism)

- 2.2.1 Dr. Craig (Birmingham)

- 2.2.2 Dr. Alvin Plantinga (Yale)

- 2.3 Reformed Arminianism (Libertarian)

- 2.4 Moderate Arm. / Calminian (Compatibilism)

- 2.4.1 ⭐ Chuck Smith

- 2.4.2 Chuck Missler

- 2.5 Systemless / Arm.

- 2.5.1 Dr. Lennox (“Oxbridge”)

- 2.5.2 Dr. Heiser (Wisconsin)

- 2.1 Classical Arminianism (Libertarian)

- Corporate Election

- Double Unconditional Predestination

- 4.1 High Calvinists (Hyper)

- 4.1.1 Demarest Against Double

- 4.1.2 Lennox Against Double

- 4.1.3 Sproul Against Double

- 4.1.4 Piper Against Double

- 4.1.5 Spurgeon Against Double

- 4.1.6 Rhodes Against Double

- 4.1.7 Craig Against Double

- 4.1 High Calvinists (Hyper)

- Universal Election in Christ

- 5.1 Barthians

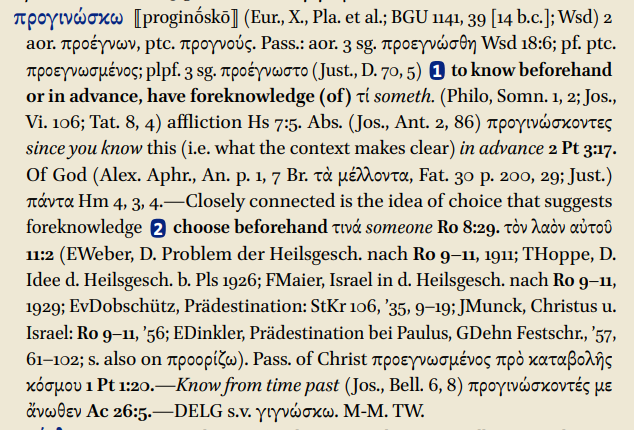

- Dictionaries & Lexicons On Proginṓskō

1. Unconditional Single Election

II. Historical Interpretations of Election.

E. Unconditional Single Election (Moderately Reformed)

Some claim that the doctrine of sovereign election to life was an Augustinian invention. Most pre-Augustinian Fathers failed to articulate a clear-cut doctrine of election for at least two reasons. (1) Many early Christian authorities reacted against rigorous Stoic and Gnostic fatalism and determinism by stressing human freedom and responsibility. From Justin Martyr (d. 165) onwards many early church authorities stated that election is conditioned on foreseen free human responses to the Gospel. Salvation, according to these Fathers, was a synergistic cooperation between the sinner and God’s Spirit. Thus Brunner astutely observed:

In a world . . . dominated by the idea of Fate, it was far more important to stress the freedom and responsibility of man than the fact that he is determined. This concern led the Early Church Fathers to the other extreme of Free Will, which they developed in connexion with the Stoic idea of autexousion as the presupposition of moral responsibility.64

In addition, (2) many early Fathers succumbed to the prevailing spirit of Hellenistic naturalism. As Thomas F. Torrance noted, “The converts of the first few generations had great difficulty in apprehending the distinctive aspects of the gospel, as for example, the doctrine of grace. It was so astonishingly new to the natural man.”65 Torrance’s studies identified “the urge toward self-justification in the second century fathers.”66 Under the influence of Greek humanism, many early Christian writers judged that God gives saving grace to those who worthily strive after righteousness. These insights help us to understand why prior to Augustine the doctrines of sovereign grace and election were muted.

Nevertheless, belief in human depravity and greater commitment to the divine initiative in salvation gradually developed in the Christian community. Tertullian (d. 220) noted that, contrary to those born in a pagan home, “the children of believers were in some sense destined for holiness and salvation.”67 Athanasius (d. 373) on occasion spoke the language of unconditional divine election. Commenting on Eph 1:3-5 and 2 Tim 1:8 10, he observed that whereas the Fall was “foreseen” the salvation of some people was predestined or “prepared beforehand.”68 In the same vein Ambrose (d. 397), whose preaching greatly influenced Augustine, wrote as follows: “God calls those whom he deigns to call; he makes him pious whom he wills to make pious, for if he had willed he could have changed the impious into pious.”69

Augustine’s (d. 430) early position on election, set forth in his exposition of Romans, was synergistic: God predestined those he foreknew would exercise faith in Christ. Yet wrestling with Scripture in the course of refuting the Pelagian heresy, Augustine changed his view and described the synergism he formerly held as the “pest of the Pelagian error.” According to Brunner, “Augustine was the only great teacher of the Early Church who gave reliable Biblical teaching on the subject of Sin and Grace.”70 The bishop insisted that although the unregenerate possess considerable psychological freedom, they lack the moral freedom (i.e., the power) to do the good. In particular, sinners cannot take the first step toward God unless enabled by God’s Spirit. Wrote the bishop, “The human will does not attain grace through freedom, but rather freedom through grace.”71 In other words, the divine commands will be fulfilled only as God himself gives the ability to perform them. Thus his prayer to God was, “Give what you command, and command what you will.”72

Augustine believed that by virtue of original sin all persons justly deserve judgment. But if God through unmerited mercy should choose to save some sinners and not others, none could charge him with acting unrighteously. Thus the bishop understood the Bible to teach that according to his good pleasure and apart from any human merit God in eternity past sovereignly chose out of the “mass of perdition” a certain number of sinners to be saved. “Grace came into the world that those who were predestined before the world may be chosen out of the world.”73 On this showing God gives to some more than they deserve, but no one gets less than they deserve. Why God chose to bless some sinners and willed to leave others in their sins has not been revealed. Yet God’s elective purpose richly displays his mercy and justice. So the bishop reasoned,

a merciful God delivers so many to the praise of the glory of his grace from deserved perdition. If He should deliver no one therefrom, he would not be unrighteous. Let him who is delivered love His grace. Let him who is not delivered acknowledge his due. In remitting a debt, goodness is perceived; in requiting it, justice. Unrighteousness is never found with God.74

Augustine believed that predestination is sometimes signified under the name of foreknowledge. “The ordering of his future works in His foreknowledge, which cannot be deceived and changed, is absolute, and is nothing but predestination.”75 Depraved sinners’ inability morally and spiritually rules out the equation of divine foreknowledge with mere prescience. “Had God chosen us on the ground that he foreknew that we should be good, then would he also have foreknown that we would not be the first to make choice of him.”76 Moreover, if God chose sinners because he foresaw that they would respond to Christ (a form of human merit), grace would cease to be grace. Such persons would have ground for boasting. “For it is not by grace if merit preceded: but it is of grace; and therefore that grace did not find, but effected the merit.”77 Finally, the bishop held that God did not foreordain persons to damnation in the same effectual way he foreordained to life. Rather, reprobation represents God’s determination that the finally impenitent will suffer the just consequences of their sins. Whereas election to life is unconditional, reprobation to perdition is conditioned on human disobedience. Thus Augustine understood predestination in an infralapsarian sense.

Thomas Aquinas (d. 1274) revived Augustine’s doctrines of sin, grace, and predestination. Considering predestination an aspect of divine providence, Thomas noted that God achieves some of his purposes by direct “operation” and others by “precept,” “prohibition,” and “permission.”78 He judged that God positively decreed the salvation of some persons, whereas he permissively decreed the perdition of others. Thomas wrote, “Some men are directed by divine working to their ultimate end as aided by grace, while others who are deprived of the same help of grace fall short of their ultimate end, and since all things that are done by God are foreseen and ordered from eternity by his wisdom . . . the aforementioned differentiation of men must be ordered by God from eternity.”79 Thomas rejected the view of certain Fathers and medieval authorities that foreknowledge of human merit or virtue is the cause of predestination to life. “The reason for the predestination of some . . . must be sought in the goodness of God” and not on “the use of grace foreknown by God.”80 Thomas likewise insisted that predestination does not destroy free will, human effort, or prayer, for God has chosen to accomplish his purposes by these secondary causes. “The salvation of a person is predestined by God in such a way, that whatever helps that person towards salvation falls under the order of predestination; whether it be one’s own prayers . . . or other good works, and suchlike, without which one would not attain to salvation.”81 As noted, reprobation is God’s permissive decision to allow sinners to persist in sin and to be punished for it. Thomas plainly wrote, “as predestination includes the will to confer grace and glory, so also reprobation includes the will to permit a person to fall into sin and to impose the punishment of damnation on account of that sin.”82

The Belgic Confession (1561) of the Reformed churches in the low countries, states that God is “merciful and just: merciful, since he delivers and preserves from this perdition all whom he in his eternal and unchangeable counsel of mere goodness has elected in Christ Jesus our Lord, without any respect to their works; just, in leaving others in the fall and perdition wherein they have involved themselves” (art. XVI). Similar is the French Confession of Faith (1559): “From this corruption and general condemnation in which all men are plunged God, according to his eternal and immutable council, calleth those whom he hath chosen by his goodness and mercy alone in our Lord Jesus Christ, without consideration of their works, to display in them the riches of his mercy; leaving the rest in this same corruption and condemnation to show in them his justice” (art. XII).

The Thirty-Nine Articles of the Church of England (1571) likewise opposed the conditional view of election. “Predestination to Life is the eternal purpose of God, whereby (before the foundations of the world were laid) he hath constantly decreed by his counsel secret to us, to deliver from curse and damnation those whom he hath chosen in Christ out of mankind, and to bring them by Christ to everlasting salvation, as vessels made to honour. Wherefore, they which be endued with so excellent benefit of God, be called according to God’s purpose by his Spirit working in due season” (art. XVII). This article adds, “the godly consideration of predestination and our election in Christ is full of sweet, pleasant, and unspeakable comfort to godly persons.”

The Westminster Confession of Faith (1647) presents the mature Reformed view on election. “Those of mankind that are predestined unto life, God, before the foundation of the world was laid, according to his eternal and immutable purpose, and the secret counsel and good pleasure of his will, hath chosen in Christ, unto everlasting glory, out of his mere free grace and love, without any foresight of faith or good works, or perseverance in either of them, or any other thing in the creature, as conditions, or causes moving him thereunto; and all to the praise of his glorious grace” (ch. 3.5).

John Gill (d. 1771), an English Baptist, believed that many Scriptures (e.g., Eph 1:4; 2 Thess 2:13; 2 Tim 1:9) plainly teach God’s unconditional election to salvation. “This eternal election of particular persons to salvation is absolute, unconditional, and irrespective of faith, holiness, good works, and perseverance as the moving causes or conditions of it; all which are the fruits and effects of electing grace, but not causes or conditions of it; since these are said to be chosen, not because they were holy, but that they should be so.”83 Gill held that sovereign election is the first link in the golden chain of salvation; forgiveness of sins, redemption, justification, and perseverance all proceed therefrom as fruit from a tree. Gill defined reprobation as God (1) passing by some sinners, thus leaving them in their sins, and (2) inflicting on them just punishment for their sins.

Charles Haddon Spurgeon (d. 1892), the Baptist pastor of London’s Metropolitan Tabernacle, explained the doctrine as follows. (1) Election derives from God’s sovereign purpose. Salvation eventuates not because humans will it in time, but because God willed it eternally. “The whole scheme of salvation, from the first to the last, hinges and turns on the absolute will of God.”84 (2) Election is entirely of grace. Guilty sinners deserve only wrath and punishment. But from eternity past God loved the elect in consequence of his own gracious purpose, not because of any foreseen merit in them. “It is quite certain that any virtue which there may be in any man is the result of God’s grace. Now if it be the result of grace it cannot be the cause of grace.”85 And (3), election is personal, not corporate. If it be unjust of God to elect a person to life, it would be far more unjust of him to elect a nation, for the latter represents an aggregate of individuals. “God chose that Jew, and that Jew, and that Jew. . . . Scripture continually speaks of God’s people one by one and speaks of them as having been the special objects of election.”86

The Baptist theologian A.H. Strong (d. 1921) held that by virtue of universal depravity God must initiate the process of salvation. The fountainhead of God’s initiative is sovereign election, defined as “that eternal act of God, by which in his sovereign pleasure, and on account of no foreseen merit in them, he chooses certain out of the number of sinful men to be the recipients of the special grace of his Spirit, and so to be made voluntary partakers of Christ’s salvation.”87 The divine election is not based on any activity of sinners, including faith, since depravity ensures that without special grace the unregenerate would bring forth no Godward movement. Moreover, God’s foreknowledge connotes not merely to “know in advance,” but more actively to “regard with favor” or “make an object of care.” In key biblical texts the words “know” and “foreknow” possess the same meaning. Strong’s measured conclusion is that “in spite of difficulties we must accept the doctrine of election.”88

This position of a single, unconditional election to life is well supported not only by historical considerations but also by the biblical data, as will be explained in the section that follows.

— Dr. Bruce Demarest (Ph.D., University of Manchester), The Cross and Salvation, Chapter Three, The Doctrine of Election, II. Historical Interpretations of Election. pp. 113-118.

1.1.1.1 Dr. J.I. Packer (PhD, University of Oxford)

- ELECTION

GOD CHOOSES HIS OWN

For [God] says to Moses, ‘I will have mercy on whom I have mercy, and I will have compassion on whom I have compassion.’ It does not, therefore, depend on man’s desire or effort, but on God’s mercy. Romans 9:15–16

The verb elect means ‘select, or choose out’. The biblical doctrine of election is that before creation God selected out of the human race, foreseen as fallen, those whom he would redeem, bring to faith, justify, and glorify in and through Jesus Christ (Rom. 8:28–39; Eph. 1:3–14; 2 Thess. 2:13–14; 2 Tim. 1:9–10). This divine choice is an expression of free and sovereign grace, for it is unconstrained and unconditional, not merited by anything in those who are its subjects. God owes sinners no mercy of any kind, only condemnation; so it is a wonder, and matter for endless praise, that he should choose to save any of us; and doubly so when his choice involved the giving of his own Son to suffer as sin-bearer for the elect (Rom. 8:32).

The doctrine of election, like every truth about God, involves mystery and sometimes stirs controversy. But in Scripture it is a pastoral doctrine, brought in to help Christians see how great is the grace that saves them, and to move them to humility, confidence, joy, praise, faithfulness, and holiness in response. It is the family secret of the children of God. We do not know who else he has chosen among those who do not yet believe, nor why it was his good pleasure to choose us in particular. What we do know is, first, that had we not been chosen for life we would not be believers now (for only the elect are brought to faith), and, second, that as elect believers we may rely on God to finish in us the good work that he started (1 Cor. 1:8–9; Phil. 1:6; 1 Thess. 5:23–24; 2 Tim. 1:12; 4:18). Knowledge of one’s election thus brings comfort and joy.

Peter tells us we should be ‘eager to make [our] calling and election sure’ (2 Pet. 1:10) – that is, certain to us. Election is known by its fruits. Paul knew the election of the Thessalonians from their faith, hope, and love, the inward and outward transformation of their lives that the gospel had brought about (1 Thess. 1:3–6). The more that the qualities to which Peter has been exhorting his readers appear in our lives (goodness, knowledge, self-control, perseverance, godliness, brotherly kindness, love: 2 Pet. 1:5– 7), the surer of our own election we are entitled to be.

The elect are, from one standpoint, the Father’s gift to the Son (John 6:39; 10:29; 17:2, 24). Jesus testifies that he came into this world specifically to save them (John 6:37–40; 10:14–16, 26–29; 15:16; 17:6–26; Eph. 5:25–27), and any account of his mission must emphasize this.

Reprobation is the name given to God’s eternal decision regarding those sinners whom he has not chosen for life. His decision is in essence a decision not to change them, as the elect are destined to be changed, but to leave them to sin as in their hearts they already want to do, and finally to judge them as they deserve for what they have done. When in particular instances God gives them over to their sins (i.e. removes restraints on their doing the disobedient things they desire), this is itself the beginning of judgment. It is called ‘hardening’ (Rom. 9:18; 11:25; cf. Ps. 81:12; Rom. 1:24, 26, 28), and it inevitably leads to greater guilt.

Reprobation is a biblical reality (Rom. 9:14–24; 1 Pet. 2:8), but not one that bears directly on Christian behaviour. The reprobates are faceless so far as Christians are concerned, and it is not for us to try to identify them. Rather, we should live in light of the certainty that anyone may be saved if he or she will but repent and put faith in Christ.

We should view all persons that we meet as possibly being numbered among the elect.

— Dr. J. I. Packer (PhD, University of Oxford), Concise Theology. 55. Election. On faith, on repentance.

1.1.1.2 Dr. Wayne Grudem (PhD, University of Cambridge)

We may define election as follows: Election is an act of God before creation in which he chooses some people to be saved, not on account of any foreseen merit in them, but only because of his sovereign good pleasure.

— Dr. Wayne Grudem (Ph.D., University of Cambridge; D.D., Westminster), Systematic Theology, Chapter 32: Election and Reprobation.

–

A. Does the New Testament Teach Predestination?

Several passages in the New Testament seem to affirm quite clearly that God ordained beforehand those who would be saved. For example, when Paul and Barnabas began to preach to the Gentiles in Antioch in Pisidia, Luke writes, “And when the Gentiles heard this, they were glad and glorified the word of God; and as many as were ordained to eternal life believed” (Acts 13:48). It is significant that Luke mentions the fact of election almost in passing. It is as if this were the normal occurrence when the gospel was preached. How many believed? “As many as were ordained to eternal life believed.”

In Romans 8:28 – 30, we read:

We know that in everything God works for good with those who love him, who are called according to his purpose. For those whom he foreknew he also predestined to be conformed to the image of his Son, in order that he might be the first-born among many brethren. And those whom he predestined he also called; and those whom he called he also justified; and those whom he justified he also glorified. 3

In the following chapter, when talking about God’s chosing Jacob and not Esau, Paul says it was not because of anything that Jacob or Esau had done, but simply in order that God’s purpose of election might continue.

Though they were not yet born and had done nothing either good or bad, in order that God’s purpose of election might continue, not because of works but because of his call, she was told, “The elder will serve the younger.” As it is written, “Jacob I loved, but Esau I hated.” (Rom. 9:11 – 13)

Regarding the fact that some of the people of Israel were saved, but others were not, Paul says: “Israel failed to obtain what it sought. The elect obtained it, but the rest were hardened” (Rom. 11:7). Here again Paul indicates two distinct groups within the people of Israel. Those who were “the elect” obtained the salvation that they sought, while those who were not the elect simply “were hardened.”

Paul talks explicitly about God’s choice of believers before the foundation of the world in the beginning of Ephesians.

“He chose us in him before the foundation of the world, that we should be holy and blameless before him. He destined us in love to be his sons through Jesus Christ, according to the purpose of his will, to the praise of his glorious grace.” (Eph. 1:4 – 6)

Here Paul is writing to believers and he specifically says that God “chose us” in Christ, referring to believers generally. In a similar way, several verses later he says, “We who first hoped in Christ have been destined and appointed to live for the praise of his glory” (Eph. 1:12).

He writes to the Thessalonians, “For we know, brethren beloved by God, that he has chosen you; for our gospel came to you not only in word, but also in power and in the Holy Spirit and with full conviction” (1 Thess. 1:4 – 5).

Paul says that the fact that the Thessalonians believed the gospel when he preached it (“for our gospel came to you . . . in power . . . and with full conviction”) is the reason he knows that God chose them. As soon as they came to faith Paul concluded that long ago God had chosen them, and therefore they had believed when he preached. He later writes to the same church, “We are bound to give thanks to God always for you, brethren beloved by the Lord, because God chose you from the beginning to be saved, through sanctification by the Spirit and belief in the truth” (2 Thess. 2:13).

Although the next text does not specifically mention the election of human beings, it is interesting at this point also to notice what Paul says about angels. When he gives a solemn command to Timothy, he writes, “In the presence of God and of Christ Jesus and of the elect angels I charge you to keep these rules without favor” (1 Tim. 5:21). Paul is aware that there are good angels witnessing his command and witnessing Timothy’s response to it, and he is so sure that it is God’s act of election that has affected every one of those good angels that he can call them “elect angels.”

When Paul talks about the reason why God saved us and called us to himself, he explicitly denies that it was because of our works, but points rather to God’s own purpose and his unmerited grace in eternity past. He says God is the one “who saved us and called us with a holy calling, not in virtue of our works but in virtue of his own purpose and the grace which he gave us in Christ Jesus ages ago” (2 Tim. 1:9).

When Peter writes an epistle to hundreds of Christians in many churches in Asia Minor, he writes, “To God’s elect . . . scattered throughout Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, Asia and Bithynia” (1 Peter 1:1 NIV). He later calls them “a chosen race” (1 Peter 2:9).

In John’s vision in Revelation, those who do not give in to persecution and begin to worship the beast are persons whose names have been written in the book of life before the foundation of the world: “And authority was given it over every tribe and people and tongue and nation, and all who dwell on earth will worship it, every one whose name has not been written before the foundation of the world in the book of life of the Lamb that was slain” (Rev. 13:7 – 8)4 In a similar way, we read of the beast from the bottomless pit in Revelation 17: “The dwellers on earth whose names have not been written in the book of life from the foundation of the world, will marvel to behold the beast, because it was and is not and is to come” (Rev. 17:8).

— Dr. Wayne Grudem (Ph.D., University of Cambridge; D.D., Westminster), Systematic Theology, Chapter 32: Election and Reprobation.

1.1.2.1 Dr. Bruce Demarest (PhD, University of Manchester)

III. The Exposition Of The Doctrine of Election.

D. Personal Election in the NT: A Major Theme

Can we find in the teachings of Jesus and the apostles evidence of personal, unconditional election? In the parable of the workers in the vineyard (Matt 20:1-16), the Lord taught that God is not obliged to deal with everyone in the same way. To those who objected that they worked all day but received the same wage as those who worked but one hour, Jesus inferred that none get less than they deserve (justice), but some get more than they deserve (grace). It is not unjust of God to give some more than their due. Elsewhere Jesus taught that of old God favored certain persons with his grace while passing by others. Thus there were many needy widows in Israel in Elijah’s day, but the prophet was sent to minister only to the widow of Zarephath (Luke 4:25-26; cf. 1 Kgs 17:8-24). In addition, there were many lepers in Israel at that time, but only one was healed of the disease, namely, Naaman the Syrian (Luke 4:27; cf. 2 Kgs 5:1-14).

Furthermore, Jesus acknowledged the Father’s sovereign right to reveal or conceal the significance of the Son’s words and works as he pleases. The Lord prayed in Matt 11:25-26, “I praise you, Father, Lord of heaven and earth, because you have hidden these things from the wise and learned, and revealed them to little children. Yes, Father, for this was your good pleasure (eudokia).” Eudokia, explaining God’s concealing and revealing activity, connotes the good pleasure of God’s sovereign will. “Eudokia expresses independent volition, sovereign choice, but always with an implication of benevolence.”103 Jesus confirmed this by adding, “No one knows the Father except the Son and those to whom the Son chooses [present subjunctive of boulomai, to “will”] to reveal him” (Matt 11:27). Thus God sovereignly chose to extend his enlightening and saving influence to some persons, while withholding it from others (cf. Matt 13:11). Although Matt 11:28-30 likely was spoken at another time in Jesus’ ministry, a universal invitation to receive Jesus (v. 28) is not inconsistent with God’s purpose to reveal himself to some. This is so because (1) Christ’s provision on the cross was universal (see chap. 4). And (2) all who respond positively to the invitation will be saved (John 11:26; Acts 10:43; Rom 10:11, 13); but tragically for themselves, depraved sinners are unresponsive to spiritual impulses—hence the need for a supernatural initiative (see chap. 5).

The adjective eklektos occurs twenty-two times in the NT, seventeen times (as a plural) in the sense of “chosen” or “elect” saints. Those envisaged are individuals within the remnant of Israel (Matt 24:22, 24, 31; Mark 13:20, 22, 27; Luke 18:7) and citizens of the church (Rom 8:33; Col 3:12; 2 Tim 2:10; Tit 1:1; 1 Pet 1:1). The elect are viewed not as an empty class, for in the preceding verses the elect cry out to God, obey Christ, are faithful to him, and reflect the fruits of the Spirit—all of which are activities of individuals, who also may be considered as a group or a class.

Although John affirmed God’s love for the entire world, the Fourth Gospel, more emphatically than the Synoptics, emphasizes God’s sovereign choice of certain persons to be saved. This is clear in John 5:21, where Jesus said to the Jews, “just as the Father raises the dead and gives them life, even so the Son gives life to whom he is pleased to give it.” Likewise in John 13:18 Jesus said to his disciples, “I am not referring to all of you; I know those I have chosen.” The Lord chose the Twelve as a group for ministry, but prior to that he chose each one, save Judas, for salvation.104

Speaking figuratively, Jesus in John 10 identified himself as the shepherd and his elect people as the “sheep.”105 John drew several important conclusions concerning the relation between the shepherd and the sheep, as follows: (1) The sheep are those people whom the Father specifically has given to the Son (v. 29). The fact that God has gifted certain persons to the Son is reiterated in John 17:2, 6, 9, 24 and 18:9, the frequency of mention suggesting that this was an important concept to John. Jesus taught more specifically in John 6:37, “All that the Father gives me will come to me” (i.e., will believe and be saved). Concerning the sheep, the Father “chose them out of the world for the possession and the service of the Son.”106 See also John 15:19, where Christ chose (eklegomai) the disciples out of the world both for salvation and service, a fact taught in similar language in John 17:6, 14, 16. The verb eklegomai (to “choose,” “select”) is used eight times of Jesus choosing disciples and seven times of God’s choice of people for eternal life (Mark 13:20; Acts 17:13; 1 Cor 1:27 [two times], 28; Eph 1:4; Jas 2:5). Carson rightly concludes that “They are Christ’s obedient sheep in his salvific purpose before they are his sheep in obedient practice.”107 (2) The shepherd died to achieve the salvation of the sheep (vv. 11, 15). Moreover, Jesus reveals himself redemptively to those the Father gave him out of the world (John 17:6, 8), and for these he intercedes in heaven. (3) The shepherd “knows” his sheep and “calls” them by name (vv. 3, 14, 27). Just as the oriental shepherd called his sheep by name, so Jesus the good Shepherd “knows” his sheep personally with a knowledge that is saving.

(4) The sheep know the voice of the shepherd and follow him (vv. 4, 27). Jesus said of those not his sheep, “you do not believe because you are not my sheep” (v. 26). We might have expected Jesus to say, “You are not my sheep because you do not believe,” but he said precisely the opposite. A sinner, then, does not become a “sheep” by believing in Jesus; rather, he or she believes in Jesus because antecedently appointed by God as one of the “sheep.” (5) Jesus’ saying—“I have other sheep that are not of this sheep pen. I must bring them also” (v. 16)—refers to specific Gentiles who de jure belonged to Christ by divine election even though de facto they had not yet come to faith. In the Johannine texts cited, the “sheep” are not an empty class, for they are said to “hear,” “know,” “believe,” “trust,” “follow,” and “love” the Shepherd—all of which are individual actions before being considered as actions of a group or a class.

The theme of election is not absent from the record of the explosive growth of the church in Acts. At Pisidian Antioch Paul acknowledged God’s corporate election of national Israel for spiritual and temporal blessings (Acts 13:17). Yet at the conclusion of Paul’s and Barnabas’ ministry in that city, Luke stated that “all who were appointed to eternal life believed” (Acts 13:48). The key word is the perfect passive participle of tassō, to “order,” “appoint,” or “ordain.” This verb occurs eight times in the NT, but only here in the sense of appointment to eternal life. F.F. Bruce suggested that the verb might be translated “enrolled” or “inscribed” in the Lamb’s book of life (cf. Luke 10:20; Phil 4:3; Rev 13:8; 17:8).108 Luke’s words clearly indicate that God’s sovereign action, be it ordaining or enrolling (or both), occurred prior to the person’s believing. The Gentile hearers believed because appointed to life; they were not appointed because they believed. All of this speaks the language of God’s sovereign election of certain persons for salvation.109

During his second missionary journey, Paul had a vision in which God encouraged him to continue preaching in Corinth notwithstanding the severe opposition he would face. Paul must persevere in sharing the Gospel, God said, “because I have many people (laos) in this city” (Acts 18:10). The heavenly message confirmed that God had chosen many persons in Corinth to be his own, and Paul’s preaching was the divinely ordained means to bring these elect to salvation. Paul’s later letters indicate that many in Corinth did come to faith and organize as Christian communities. Leon Morris comments concerning the “people” in Corinth: “They had not yet done anything about being saved; many of them had not even heard the gospel. But they were God’s. Clearly it is he who would bring them to salvation in due course.”110

In Rom 8:28-30 Paul delineated the full circle of salvation, which clinched his argument concerning Christians’ hope of heavenly glory (vv. 18-27).

And we know that in all things God works for the good of those who love him, who have been called according to his purpose. For those God foreknew he also predestined to be conformed to the likeness of his Son, that he might be the firstborn among many brothers. And those he predestined, he also called; those he called, he also justified; those he justified, he also glorified.

We observe, first, that the foundation of the Christian’s calling to salvation is God’s prothesis, meaning “purpose,” “resolve,” or “decision” (Rom 9:11; Eph 1:11; 3:11; 2 Tim 1:9). The believer’s hope of future glory is grounded not in his own will but in the sovereign, pre-temporal purpose of God.

The first of the aorist verbs in the passage is the word proginōskō, to “foreknow,” “choose beforehand.”111 With humans as subject the word means to “know beforehand” (Acts 26:5; 2 Pet 3:17). With God as subject the verb could mean either prescience or foreloving/foreordaining (Rom 8:29; 11:2; 1 Pet 1:20). The foundational verbs yāda‘ and ginōskō often mean to “perceive,” “understand,” and “know.” But they also mean “to set regard upon, to know with particular interest, delight, affection, and action. (Cf. Gen 18:19; Exod 2:25; Ps 1:6; 144:3; Jer 1:5; Amos 3:2; Hos 13:5; Matt 7:23; 1 Cor 8:3; Gal 4:9; 2 Tim 2:19; 1 John 3:1).”112 The verb ginōskō thus can convey God’s intimate acquaintance with his people, specifically the fact that they are “foreloved” or “chosen.” This latter sense is evident in the following Pauline sayings: “the man who loves God is known by God” (1 Cor 8:3); “but now that you know God—or rather are known by God” (Gal 4:9); and “the Lord knows those that are his” (2 Tim 2:19).

The verb proginōskō in Rom 8:29 and 11:2 contextually could be taken in either of the two senses, i.e., prescience or foreordination. But given the strongly relational Hebrew background to the word, the unambiguous sense of proginōskō in 1 Pet 1:20 (see below) and prognōsis in Acts 2:23 and 1 Pet 1:2 (see below), and the whole tenor of Paul’s theology, the probable meaning of proginōskō with God as subject is to “know intimately” or “forelove.”113 F.F. Bruce concurs with this judgment. Concerning Rom 8:29, he wrote, “the words ‘whom he did foreknow’ have the connotation of electing grace which is frequently implied by the verb ‘to know’ in the Old Testament. When God takes knowledge of his people in this special way, he sets his choice upon them.”114 To the preceding considerations we add that the biblical language of foreknowledge is always used of saints, never of the unsaved. Moreover, what God “foreknows” is the saints themselves, not any decision or action of theirs. Thus divine election is according to foreknowledge (foreloving), not simply according to foresight (prescience).

Paul continues in the Romans text: “For those God foreknew he also predestined [proōrisen] to be conformed to the likeness of his Son . . .” (v. 29). The verb proōrizō, to “decide beforehand,” or “predestine,” occurs six times in the NT in the sense of God’s predetermined plan of salvation, Christ’s sufferings, or gracious election to life (Rom 8:29-30; 1 Cor 2:7; Eph 1:5, 11). Those on whom God in eternity past set his affection, he sovereignly chose for life.

Return for a moment to the larger picture of the golden chain of salvation presented in Rom 8:29-30. The verbs “foreknew,” “predestined,” “called,” “justified,” and “glorified” are in the aorist tense, which denotes God’s prior determination marking these future events with certainty. Moreover the verbs grammatically are in exact sequence; thus if the election and the calling were exclusively corporate, so also would be the justification and the glorification. But God does not justify an empty class; he justifies individuals within the class who are moved to saving faith in Christ. Similarly, it is individuals who possess the Spirit (v. 23), who “groan inwardly” awaiting the day of glorification (v. 23), who exercise “hope” (v. 24), and who display patience (v. 25). Clearly these are spiritual experiences of individual Christians who, when considered aggregately, constitute the class of believers. Thus the focus of the circle of salvation is both corporate and individual.115

Romans 9–11 is an important text for understanding God’s saving purpose for Jews and Gentiles. Paul first recalled Israel’s glorious spiritual heritage: “Theirs is the adoption as sons; theirs the divine glory, the covenants, the receiving of the law, the temple worship and the promises” (Rom 9:4; cf. v. 5). Given these lofty privileges, why are so few Jews saved? Has God’s purpose for his people failed? To these questions Paul responded with a firm no! The fact is, he continued, “not all who are descended from Israel are Israel. Nor because they are his descendants are they all Abraham’s children” (vv. 6-7). The existence of a believing remnant—a circle of elect ones—within ethnic Israel attests that God’s purpose has not been frustrated, that his promise has not failed.

Paul further indicated God chose Isaac over Ishmael (vv. 7-9) and Jacob over Esau (vv. 10-13) before they were born or had done good or evil “in order that God’s purpose [prothesis] in election [eklogē, “picking out,” “election,” “selection”] might stand” (v. 11). To support this argument. Paul quoted from Mal 1:2-3, “Jacob I have loved, but Esau I have hated.” Cranfield concludes that “loved” and “hated” here denote election and rejection respectively. 116 Paul’s emphasis clearly is upon God’s sovereign purpose, not man’s response. God’s election of Isaac and Jacob is individual unto salvation and not merely corporate (Israel and Edom) in respect of earthly privileges, since in vv. 9-13 each of the children—their birth and their deeds—is in the foreground.117 Moreover, in v. 24 Paul stated that God chose and called not only individuals from among the Jews (such as Isaac and Jacob) but also individuals from among the Gentiles. A further factor is the flow of Paul’s argument. He sought to show that in spite of the unbelief of ethnic Israel God’s saving purpose has not failed, as confirmed by the election of a believing remnant exemplified by Isaac and Jacob. To say that God’s purpose for Israel remains valid, notwithstanding the unbelief of ethnic Israel in general, because God chose the line of Isaac and Jacob for temporal blessings is merely to restate the historical problem and to solve nothing.118

To this affirmation of God’s sovereign election of a remnant within ethnic Israel, Paul’s critics levied two objections. First, God would be unjust in his dealings (vv. 14-18). This objection would be of little force if the issue at hand were merely the choice of ethnic Israel for earthly privileges. But note that Paul’s response to the objection was an emphatic, “Not at all!” (v. 14). Although finite beings do not comprehend God’s elective purpose, God reserves the right to exercise mercy upon whom he chooses. So the apostle appealed to Yahweh’s words to Moses, “I will have mercy on whom I have mercy, and I will have compassion on whom I have compassion” (v. 15; cf. v. 18).119 God is not unjust to give a person more than he deserves while permitting the unsaved to continue in their chosen path of sin, any more than it is not unjust of an earthly governor to pardon one criminal and not another. Concerning the divine election of a remnant Paul wrote, “It does not, therefore, depend on man’s desire or effort, but on God’s mercy” (v. 16). The decisive factor concerning who will be saved is God’s sovereign will, not human volition.

The second objection levied was that if God is sovereign in election and hardening, no one could be judged blameworthy (vv. 19-24). Paul responded sternly to the arrogant objector: “who are you, O man, to talk back to God?” (v. 20). Appealing to the OT imagery of the potter and the clay (Jer 18:2-6), Paul argued that as the potter has the right to mold the clay as he wills, so God has the sovereign right to bestow more grace on one of his creatures than on another (v. 21). Paul’s reference to “the objects of his mercy, whom he prepared in advance for glory” (v. 23) clearly depicts his sovereign, pre-temporal election of some for heavenly destiny.120 Pinnock has argued in the light of the potter and the clay analogy that God “has a great deal for which to answer.”121 The crucial issue is, Must the all-perfect God answer to finite and feeble-minded humans, or must we mortals bow before and answer to a sovereign, just, and allwise God?

In the second section of our extended text, Rom 9:30–10:21, Paul argued that the fact of sovereign election, as expounded from the OT, does not eliminate the individual’s responsibility for making the right choice. Quoting from Joel 2:32, Paul wrote, “Everyone who calls on the name of the Lord will be saved” (10:13). Personal response to the Gospel message is necessary if one would be saved. Paul continued that the Gospel has been published widely and to Jews first. “But not all the Israelites accepted the good news” (v. 16). Why not? Because they sought righteousness by law-keeping rather than by faith in the crucified and risen Messiah. The Lord holds unbelieving Israel morally responsible for their unbelief.

The third section, Rom 11:1-29, explains God’s purpose for the future of Israel and the Gentiles. Paul again refuted the notion that God has rejected Israel: “God did not reject his people, whom he foreknew” (v. 2a). The objects of God’s foreknowledge are the Jewish people, often disobedient and faithless and without praiseworthy responses on their part. Rom 11:2 thus better fits the conclusion reached above—i.e., that God’s foreknowing is equivalent to his foreloving or foreordaining. The NT frequently cites the very close relationship that exists between God’s loving and his choosing (Eph 1:4; Col 3:12; 1 Thess 1:4; 2 Thess 2:13). That God has not forsaken his people is evidenced by the fact that “at the present time there is a remnant chosen by grace” (v. 5). The existence of an elect remnant within the chosen nation is the outcome of God’s sovereign and gracious purpose. God formed the remnant by a personal election within the corporate election to yield a spiritual seed within the institutional people. We underscore the conclusion of Jewett: “Israel was elect in a double sense: in an outward and temporal sense, the nation, as a nation, was elect; in an inward, personal, and eternal sense, a faithful remnant was elected.”122 To illustrate this choice of an elect remnant, Paul pointed to himself (v. 1b) and to 7,000 faithful souls in Elijah’s day who would not bow before Baal (vv. 2b-4). The nation as a whole failed to obtain spiritual blessing (v. 7), “but the elect (eklogē) did [obtain it],” not by works but by grace (v. 6). We defer discussion of the salvation of many Gentiles and eventually “all Israel” (v. 26) to the volumes in this series on the church and eschatology.

The apostle, however, concluded his treatment of God’s sovereign elective purpose for Jews and Gentiles with a hymn of praise (vv. 33-36). God’s gracious choice of certain Jews and Gentiles to be saved lends itself more to doxology than to precise rational analysis. The salvation of the remnant is the result of the “wisdom,” “knowledge,” “judgments,” and “mind” of the Lord.123 God’s sovereign purpose of mercy and grace to sinners is so grand and exalted that the only fitting response on the part of feeble humans is humble praise and adoration. “For from him and through him and to him are all things. To him be the glory forever!” (v. 36).

In Gal 1:15-16 Paul wrote that “God, who set me apart from birth and called me by his grace, was pleased to reveal his Son in me so that I might preach him among the Gentiles. . . .” Paul made it abundantly clear that prior to his conversion he hated the church and did his utmost to destroy it (Gal 1:13, 23; cf. Acts 9:1-2, 13-14; 22:4-5; 26:10; 1 Tim 1:13). Yet he also affirmed that God in grace took the saving initiative in his rebellious life. Thus the Father was pleased to separate him from birth—the word aphorisas (“separated”) being related to proōrisas (“predestinate”)—and to reveal his Son to him (cf. 2 Cor 4:6). Only then did the Lord commission Paul for Gospel ministry. The apostle thus attested God’s act of separation in eternity past for salvation and in time for service. As he testified in Gal 2:20, God’s saving action toward him was profoundly personal. Thus Paul saw himself (1) personally loved by Christ (“who loved me”), (2) personally justified (“I live by faith in the Son of God”), (3) personally regenerated (“Christ lives in me”), and (4) personally united with the Savior (“crucified with Christ”). Four times in this one verse Paul used the first-person pronoun (egō, emou, me, emoi). Jewett’s comment again proves instructive: “The individual quality in God’s electing love is reflected in the use of the singular personal pronoun in Scripture. . . . To be elect is to be aware that God has fixed his love on me, called me by name, given me a new name (Rev 2:17), and inscribed my name in the Book.”124 God had a plan for Saul/Paul and worked efficiently to bring him to faith in Christ. The same could not be said for God’s relation to Judas, Pilate, or Herod.

A comprehensive Pauline text dealing with election is Eph 1:3-14, which we analyze as follows. (1) The source of election: “the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, who has blessed us in the heavenly realms with every spiritual blessing in Christ” (v. 3). Election is a monogeristic operation of God, not a synergism (cf. 2 Tim 1:9). (2) The fact of election: “we were also chosen, having been predestined according to the plan of him who works out everything in conformity with the purpose of his will” (v. 11; cf. vv. 4-5, 9). Paul’s election words in the preceding verses are heaped one upon the another, powerful and descriptive of what God himself accomplishes: eklegō, to “choose out,” “select;”125 kleroō, to “choose,” “destine”; proorizō, to “foreordain,” “predestine”; protithēmi, to “purpose,” “intend”; prothesis, “plan,” “purpose,” “resolve;”126 boulē, “an intention” or “deliberation” (with emphasis on the deliberative aspect of the decision;127 thelēma, “will” or “intention”—i.e., “God’s eternal and providential saving will,”128 with emphasis on the volitional aspect or the will in exercise; and eudokia, “good pleasure,” “act of the will”—a choice grounded in God’s sovereign purpose.129

(3) The time of election: from eternity past, i.e., “before the creation of the world” (v. 4; cf. 2 Thess 2:13; 2 Tim 1:9). Salvation is the unfolding of God’s eternal purpose. “The Scriptures say that God chose us in Christ from before the foundation of the world, not that he saw us from before the foundation of the world as choosing Christ.”130 (4) the objects of election: “we” (v. 7) or “us” (vv. 3-6, 8-9). Paul envisaged the elect both in their corporate standing as the church and in their individuality. The latter is clear in Rom 16:13, where Paul wrote, “Greet Rufus, chosen (ton eklekton) in the Lord,” and in 1 Pet 1:1, discussed below. The people of God are viewed both in their unity and in their diversity (Rom 12:4-5; 1 Cor 10:17; 12:12, 20; Eph 4:25; 5:30; Col 3:15). Berkouwer made this important observation: “We are repeatedly struck by the lack of tension between the election of the individual and the election of the church…. The life of the individual does not dissolve into the community”131 (emphasis added). Every social unit must be defined in terms of the individuals that comprise it. The NT designates Christians as “believers,” “saints,” and “elect.” No one doubts that it is the individual that believes and is sanctified. So ultimately it is the individual who is loved and chosen by God. Luther captured this individual dimension of salvation, often obscured by corporate advocates, when he wrote, “You must do your own believing, as you must do your own dying.”132

(5) The sphere of election: “in Christ” (vv. 3-7, 9, 11; 3:11; 2 Tim 1:9). Arminians interpret “in Christ” as elect according to our quality as believers. Predestination “in Christ,” however, affirms God’s purpose to effect salvation through the person and work of Jesus Christ (vv. 5, 7; cf. Rom 6:23b; 2 Tim 1:9b). “Christ is the medium for the imparting of grace.”133 The phrase “in Christ” positively excludes a works-effected salvation. (6) The motive of election: God’s freely conceived and unconditional love. So Paul wrote, “in love he predestined us” (vv. 4-5). (7) The impartiality of election: “in accordance with his pleasure and will” (v. 5; cf. Rom 2:11; 11:34). God’s choice was not motivated by the faintest hint of favoritism. Finally, (8) the goal of election: that believers might “be holy and blameless in his sight” (v. 4), and that they might live “to the praise of his glorious grace” (v. 6). The outcome, not the condition, of election is righteousness of life.

To encourage Thessalonian Christians who were severely persecuted, Paul wrote that the God who had chosen them for salvation from eternity past and called them to Christ would sustain them in their present trials (2 Thess 2:13-14). Sorely tempted to renounce Christ, the believers would have found little consolation in the reminder that it was they who had chosen God. Rather, the supreme encouragement in a situation where their human resources were failing was that God had chosen them for an enduring salvation. So the apostle wrote, “we . . . thank God for you, brothers loved by the Lord, because from the beginning God chose [eilato] you to be saved through the sanctifying work of the Spirit and through belief in the truth.” The middle voice of a verb denotes the subject acting with respect to itself. Here the aorist middle indicative of haireomai (to “choose,” “prefer,” “decide”) “emphasizes . . . the relation of the person chosen to the special purpose of him who chooses. The ‘chosen’ are regarded . . . as they stand to the counsel of God.”134 See also 1 Thess 1:4-5, where the saints’ response to the Gospel was evidence of their prior election. Election in eternity past was actualized in time by the sanctifying work of the Spirit and the Thessalonians’ belief in the Gospel as preached by Paul. 2 Thess 2:13 (NRSV) indicates that God actively chose them specifically “for salvation” (eis sōtērian). Paul also stated this truism in 1 Thess 5:9 when he wrote, “God. . . [appointed] us . . . to receive salvation” (eis peripoiēsin sōtērias).135 To the Christian’s experiential question, Why am I a Christian?, the biblically faithful answer must be, Because God chose me.

James also stated that the initiative in salvation lies wholly with the sovereign God: “He chose [boulētheis] us to give us birth through the word of truth” (Jas 1:18). Jude 1 affirmed the same in its description of Christians as people “called,” “loved,” and “kept” by God. Observe that it is fundamentally the individual (and by extension the class) who is “loved” and “kept” by God; so also it is the individual who is “called” by God. Peter viewed the body of Christ as the new people of God (1 Pet 2:9-10); yet within this new entity he saw the election of individuals to salvation. So Peter wrote his first letter to “God’s elect [eklektois], strangers in the world, scattered” throughout much of Asia Minor (1 Pet 1:1). Since individuals, not a class, scatter or are dispersed, Peter had in mind an aggregate of individuals, not an empty class. The elect ones “have been chosen according to [kata] the foreknowledge [prognōsin] of God the Father, through (en) the sanctifying work of the Spirit, for [eis] obedience to Jesus Christ and sprinkling by his blood” (v. 2). Several comments on this verse are in order. (1) The preposition kata indicates the basis of divine election—namely, the divine foreknowledge. In context, prognōsis denotes the divine foreloving or foreordaining, or as Selwyn stated, God’s “knowing or taking note of those whom He will choose.”136 That God’s foreknowledge of Christians likely indicates more than prescience is confirmed by Peter’s statement that Christ “was chosen (perfect passive participle of proginōskō) before the creation of the world” (1 Pet 1:20; “He was destined,” RSV, NRSV; cf. Acts 2:23). 1 Pet 1:2 says nothing about Christians being chosen on the basis of foreseen faith. (2) The preposition en signifies the means by which eternal election was effected in time—i.e., by operation of the Spirit. And (3) the preposition eis denotes the goal or outcome of election—i.e., obedience to Christ and the application of his atoning benefits. Peter did not state that those who obey Christ are elect, but that the elect proceed to obey Christ. See also Jas 2:5.

In 2 Pet 1:10 the disciple wrote to the dispersed believers, “Therefore, my brothers, be all the more eager to make your calling and election [eklogē] sure. For if you do these things, you will never fall.” Truly it is not the undifferentiated group that falls or fails to persevere, but individuals who are here considered aggregately. Moreover, the brothers confirm their calling and election by cultivating the qualities listed in vv. 5-7, namely, “faith,” “goodness,” “knowledge,” “self-control,” “perseverance,” “godliness,” “brotherly kindness,” and “love.” These too are activities of individuals, not of an empty group or class. Therefore if we talk of the election of a class, it must be as the sum of elect individuals.

— Dr. Bruce Demarest (Ph.D., University of Manchester), The Cross and Salvation, Chapter Three, The Doctrine of Election, III. The Exposition Of The Doctrine of Election. pp. 124-135.

1.1.2.2 Dr. Michael F. Bird (PhD, University of Queensland)

I submit that divine foreknowledge is determined by predestination rather than vice versa. God foreknows those who will be saved because he has predestined them to salvation — Michael F. Bird (Ph.D., University of Queensland), Evangelical Theology. 2nd ed. pp. 568-9.

–

Scripture contains ample reference to God’s determining things ahead oftime. According to the psalmist, “All the days ordained for me were written in your book before one of them came to be” (Ps 139:16). Similarly in Isaiah we find, “Have you not heard? Long ago I ordained it. In days of old I planned it; now I have brought it to pass, that you have turned fortified cities into piles of stone” (Isa 37:26). In Peter’s speech in Acts, he says that Herod, Pontius Pilate, and the Jerusalemites conspired againstJesus, and they “did what your [God’s] power and will had decided beforehand should happen” (Acts 4:28, italics). In Paul’s speech in the Areopagus, he tells his audience that God has “appointed” the times and places of the peoples and nations (Acts 17:26). It seems that God knows the future only because he has preordained it. — Michael F. Bird (Ph.D., University of Queensland), Evangelical Theology. 2nd ed. p. 566.

1.1.3 Moderately Reformed Compatibilism

Compatibilism is the belief that free will and determinism are compatible and can coexist in a philosophical sense simultaneously. In a theological context, God’s sovereignty and human responsibility would be mutually compatible. In other words, God is absolutely sovereign and humans have libertarian free will. This group of theologians are compatibilists that hold moderately reformed views in the sense that they do not view election as being based on human free will or foreknowledge of forseen faith, but they still acknowledge that human free will exists.

Prredestination, Election, & Determinism

The terms used in the debate do no possess the same meaning from author to author, and so preliminary definitions are in order. ‘Predestination’ in this book refers to the fore-ordination of events by God. ‘Election’ refers to soteriological predestination, with the added caveat that no judgement as to the nature of the salvation is presupposed by the terms themselves. Because predestination, by this definition, has God as the one who predestines, it is to be distinguished from ‘determinism’, which supposes that all is in principal completely predictable according to the universal laws of nature, but which does not trace such fixedness to God. — Dr. D.A. Carson (PhD, University of Cambridge), Divine Sovereignty & Human Responsibility. p. 3.

Human Responsibility, Free Will, Freedom

‘Responsibility’ here means a personal relationship of obligation and accountability toward (usually) God. That the relationship is personal and accountable presupposes some measure of real freedom; but possible approches to ‘free will’ are best considered inductively. ‘Freedom’ and ‘free will’ may therefore be excluded from initial definitions. — Dr. D.A. Carson (PhD, University of Cambridge), Divine Sovereignty & Human Responsibility. p. 3.

1.2.1.1 Dr. Hugh Ross (PhD, Astrophysicist at University of Toronto)

Question of the Week: Of the main sotierology models within evangelicalism to which do you adhere: Calvinism, Arminianism, or Traditionalism?

My Answer: These three models are each broad in their doctrinal beliefs. However, all Calvinists believe in the supremacy of God’s will over human will and that God has predetermined everything that will happen in the future. In particular, Calvinists believe that every human God chooses to receive salvation indeed will receive salvation and that only humans that God has called to be saved will be saved. All Arminianists believe that all humans possess free will and that the free will of humans is the deciding factor on who will be saved. In particular, only humans who choose to be saved will be saved. Traditionalists tire of the acrimony and debate that has existed between Calvinists and Arminianists. They call for unity through a focus on the doctrines that both Calvinists and Arminianists uphold. Both Calvinists and Arminianists counter that what divides them are critically important doctrines for the Christian faith.

I wrote an entire book addressing the posed question: Beyond the Cosmos, now in its third edition. Anyone can get a free chapter at reasons.org/ross. In that book I explain why each of Calvinism, Arminianism, and Traditionalism are inadequate by themselves to address all that the Bible teaches on sotierology and our relationship with Christ. I point out, for example, that the Bible teaches that both divine predetermination and human free will simultaneously operate. I explain why there is no possible resolution of this paradox within the spacetime dimensions of the universe. However, the Bible teaches and the spacetime theorems prove that God created the cosmic spacetime dimensions and in no way is limited by them. I show three different ways how the paradox of divine predetermination and human free will can be resolved in the extra- and trans-dimensional context of God. I also show how several other biblical paradoxes can be resolved from God’s extra-/trans-dimensional perspective.

— Dr. Hugh Ross (Ph.D., Astrophysicist at the University of Toronto)

1.2.1.2 Dr. D.A. Carson (PhD, University of Cambridge)

- 1.2.1.2.1 Men As Responsible

- 1.2.1.2.2 God As Sovereign

I frankly doubt that finite human beings can cut the Gordian knot; at least, this finite human being cannot. The sovereignty–responsibility tension is not a problem to be solved; rather, it is a framework to be explored. — Dr. D.A. Carson (PhD, University of Cambridge), Divine Sovereignty & Human Responsibility. p. 2.

1. Men face a plethora of exhortations and commands The point is so obvious that it scarcely requires making. From the first prohibition in Eden (Gen. 2.16f.), through commands to individuals like Noah and Abraham-whether commands to build an ark or to walk blamelessly (Gen. 6.13ff.; 17.1-6) to the prescriptions laid on the covenant people, human responsibility is presupposed. Such prescriptions include the details of tabernacle construction and acceptable cultic worship, as well as the broad ‘moral’ commandments, specific civil legislation, and sweeping commands to be holy. The requirements of God touch all of life, not merely worship abstracted from life, with the result that his people are to be different from the surrounding nations. (Cf. Exod. 20.3ff.; Lev. 11.44f.; 20.7f.; 22.31-3; Deut. 10.12f.; 12.29-31; 14.1f.; Isa. 56.1; Jonah 1.2; Mic. 6.8; Mal. 3.10; Ps. 119.1-3; etc.) In addition, men are exhorted to seek the Lord: this theme is particularly reiterated by the prophets (e.g. Isa. 55.6f.; Amos 5.6-9; Zeph. 2.3). The Tabernacle itself was established as a place where men might seek Yahweh (Exod. 33.7). Deuteronomy encourages the people to believe that after they have rebelled and God has turned away from them, they will find him again when they seek for him (Deut. 4.26-32; 30.1-3). God has only good purposes for those who seek him (Ezra 8.22f.). Asa is bluntly told, “The LORD is with you, while you are with him. If you seek him, he will be found by you, but if you forsake him, he will forsake you’ (2 Chr. 15.2). The Psalms frequently spell out the same message (e.g. 105.4; 145.18).

2. Men are said to obey, believe, choose God may choose Abraham and promise him great blessing; but it is Abraham who believes the promise (Gen. 15.4-6) and obeys God’s voice (Gen. 22.16-18). In Exodus the Israelites agree to be obedient (Exod. 19.8; 24.3-7). Frequently they do ‘just as God commanded’ (e.g. Exod. 16.34; 38-40; Num. 8.20; 9.8, 23; 31.31); indeed, even with a willing heart (Exod. 35.5, 21). The Israelites are told to choose Yahweh (Deut. 30.15-19; Josh. 24.14-25; 1 Kgs. 18.22), and indeed do so (Josh. 24:22); and when instead they serve the gods of pagan neighbours, it is because they have chosen them (Judg. 10.14). They make solemn vows (e.g. Num. 21.2; Judg. 11.30f.). Two ways are set before the people (cf. Lev. 26.1-45; Deut. 28; 30.15-20; Ps. 1), and the way that brings blessing turns on human repentance and obedience. Similarly in human relation- ships, there is a certain freedom of choice (e.g. Num. 36.6). All such categories presuppose human responsibility.

3. Men sin and rebel From the first disobedience onward, the pages of the Old Testament are blotched with every conceivable form of trans- gression. The imagination of men turns constantly toward evil; and this description (Gen. 6.5) could rightly be applied to more than antediluvian people. The resources of language are exhausted as the loathsomeness of particularly vile men or periods is ruthlessly exposed (e.g. Gen. 18.20f; Exod. 32.7-14; Num. 16.3-35; Judg. 19f.; Deut. 1.26ff.; 9.22-4; 2 Kgs. 17.34-41; Isa. 1.2ff.; 30.9ff.; Jer. 2.13ff.; 5.3; 6.16f.; 42.10ff.; Ezek. 8; 22; Hos. 2.7; 4.2, 7, 13). The people ‘corrupt themselves’ (Exod. 32.7), or do what is right in their own eyes (Judg. 17.6; 21.25). Such language is incongruous if men are not rightly held accountable for what they are and do.

4. Men’s sins are judged by God Men are not held to be responsible in some merely abstract fashion; they are responsible to someone. God is the judge of all the earth, of all nations; men are ultimately answerable to him. Drumming through the Old Testament is the motif of judg. ment. Yahweh reacts against sin with terrible punishments. Even those parts of the Old Testament which wrestle with the fact that God’s judgments are not always immediate and temporal do not diminish this theme, but prepare the way for a heavier accent on the certainty of eschatological judgment. (Cf. Gen. 6-8; 18.25; Exod. 23.7; 32.7-12, 26-35; Lev. 10.1ff.; Num. 11.1ff.; 16.3-35; Deut. 32.19-22; Josh. 7; Judg. 2.11ff.; 3.5ff.; 4.1ff.; 1 Sam. 25.38f.; 2 Sam. 21.1; 2 Kgs. 17.18ff.; 22.15ff.; 23.26ff.; Isa. 14.26f.; 66.4; Jer. 7.13f.; Ezek. 5.8ff.; 25-28; Nahum 3.1ff.; Hag. 1.9-11; Zech. 7.12-14; Ps. 75.6f.; 82.8; 96.10; Eccles. 11.9; 12.14.) Human accountability is all the more deeply stressed when the writers insist God is longsuffering and slow to anger (Exod. 34.6; Num. 14.18; Joel 2.13; Jonah 4.2; Ps. 86.15; 103.8; Neh. 9.17). In short: divine judgment presupposes human responsibility.

5. Men are tested by God The testing of men is often couched in the anthropomorphic language by which Yahweh declares he wishes to know what is in men’s hearts (e.g. Gen. 22.12; Exod. 16.4; Deut. 13.1-4; Judg. 2.20-3.4; 2 Chr. 32.31); but this is not invariably so (e.g. Ps. 11.5; 105.19). From the examples cited in these references it is clear that God’s tests can be directed either toward individuals or toward his entire people. Such tests entail no guaranteed result: Abraham passes his test, Hezekiah does not. Some tests spring out of God’s judicial discipline of sin previously com- mitted by the people (e.g. Judg. 2.20-3.4). In any case the testing inevitably concerns the obedience and faithfulness of those tested, and presupposes their accountability for such virtues.

6. Men receive divine rewards This point overlaps the last two. Judgment, after all, may be viewed as negative reward; and the tests of the Old Testament entail positive reward for those who pass them. These positive rewards now concern us. The blessing of Abraham is related to his obedience (Gen. 22.18). The midwives of the captive Israelites are blessed because they feared God (Exod. 1.20f.). The The people are assured that if they will obey they will see Yahweh’s glory (Lev. 9.6); if they keep the law they will live (18.3-6). Caleb receives special treatment because he follows Yahweh fully (Num. 11.32; Josh. 14.9, 14). God will thrust out the rest of the Canaanites, but the people must be obedient (Josh. 23.4-9). If the people will return to Yahweh, acknow- ledging their sin, he will bless them (Jer. 3.12-22; 7.3-7, 23-28). God will stuff the storehouses of the people if they will be faithful in the matter of tithes and offerings (Mal. 3.10f.). Much of the prophetic preaching looks forward to great blessing, contingent upon the obedience of the people (e.g. Isa. 58.10-14; Jer. 7.23; Zech. 6.15). Such promises appear utterly ridiculous if human responsibility is not presupposed.

7. Human responsibility may arise out of God’s initiative Whatever the implications of election in the Old Testament (infra), it is clear that although election brought high privilege to Israel, it also laid heavy responsibility on her, and was charged with constraint, which she could only disclaim to her hurt. Here is responsibility arising out of Yahweh’s choice. The prophets especially make it clear that the privilege of election by Yahweh brings with it extensive demands on his people. Judge of all the nations Yahweh may be; but Amos insists that Yahweh’s ‘knowing’ of Israel in particular is in fact the basis of special and imminent judgment (Amos 3.2). The responsibility which Israel faces stems not so much from God’s naked choice of the nation, as from that allegiance to him which is entailed by election. Once the law is given, allegiance to Yahweh and obedience to the law can scarcely be distinguished. Hence, responsibility to obey all that Yahweh has commanded is based on, and arises out of, the election of Israel. (Cf. Exod. 19.4-6; Deut. 4.5-8; 6.6ff.; 10.15ff.; 11.7-9; Hos. 13.4; Mic. 3.2.)

The Wisdom literature never descends to the level of secular common sense, partly because the demands of Yahweh lie inextricably interwoven with others in which no explicit reference to Yahweh is made, but even more because, in the latter cases, it is presupposed that the fear of Yahweh is fundamental to wisdom (cf. Prov. 9.10; 16.7-12)-this Yahweh who, it is understood from Deuteronomy on, always commands what is for the good of his people (Deut. 6.24).2 Privilege stemming from divine grace enhances responsibility, and never reduces it.

8. The prayers of men are not mere show-pieces That God has spoken propositionally was a fundamental conviction of the Old Testament writers. But the intercourse between God and man involved man speaking to God as well Man’s voice in addressing God is never the pre-programmed recording of the robot; it is the adoration of worship, the cry of desperation, the relief of gratitude, the petition of the needy. The personal, accountable character of man is nowhere more clearly seen than in his prayers of intercession and petition.

Some such prayers are well-planned, even if intense (e.g. 1 Kgs. 8.46ff.; 2 Chr. 7.12-22). Others are the cries of desperation (e.g. Exod. 32.7-13, 31f.; Josh. 10.11-14). Some are answered positively (e.g. Gen. 25.21; Judg. 6.36-40; 1 Kgs. 3.6-9; 2 Kgs. 20.1-6; Isa. 38); and others are categorically turned down (e.g. Jer. 14.11; 15.1f.; 1 Sam. 15.35-16.1). Some prayers magnify the wretchedness of sin (e.g. Exod. 32; Deut. 9.25ff.), others the greatness of Yahweh and his love for Israel (e.g. Josh. 10.12-14). In any case, the idea that men may prevail in prayer with God again presupposes human responsibility, and a significant measure of human freedom; for such language depicts the interplay of personalities, not the determinism of machines.

9. God utters pleas for repentance The pre-exilic prophets unite in presenting Yahweh as the one who finds no pleasure in the death of the wicked, who pleads with men to return to him and avoid the otherwise inevitable and horrible consequences of their own rebellion. When he does afflict his people, it is unwillingly. (Cf. Isa. 30.18; 65.2; Lam. 3.31-6; Ezek. 18.30-32; 33.11; Hos. 11.7ff.) Even when all due allowance is made for anthro- pomorphisms, the necessary conclusion is that men are viewed as responsible creatures whose rebellion Yahweh is enduring with merciful if painful forbearance, and punishing with reluctant wrath.

10. Concluding remarks Qoheleth reminds us that God made men upright, but they have sought out many ‘devices’ (Eccl. 7.29). God is customarily in some way removed from man when he sins. This pattern of preserving a distance between God and sin comes to the fore in God’s rejection of sinners, a rejection which, far from asserting God’s contingency, underlines rather the certainty of his holy judgment (especially when divine omniscience is in view: e.g. Isa. 29.15f.; Jer. 16.17f.) or the real guilt of the transgressor (e.g. 1 Sam. 15.23b). When instead God is implicated as the cause (in some sense) of a particular sin, there are invariably other factors involved, notably a display of his judicial hardening or of his sovereign hand behind a major event of salvation history.

It is instructive to observe how the various motifs discussed above function in the Old Testament writings. Injunctions to choose Yahweh, and the tests which God administers to men and nations, are not given to evoke metaphysical definitions concerning the nature and limitations of human freedom, but to command committed assent and obedience. When a right choice is made (e.g. Josh. 24.22), it tends to become an incentive for continued faithfulness and the fresh abandonment of encroaching idolatry. Similarly the positive rewards which follow faith and obedience (e.g. Gen. 22.18; Exod. 1.20f.; Num. 11.32; Josh. 23.4-9) become motivation for increased and continuing obedience, not grounds for boasting once they have been attained. At most, conduct pleasing to God may function in some petitions as the ground for vindication and divine approval (as in some psalms-e.g. 34, 69, 79, 109, 137; cf. also Neh. 5.19; 13.14, 22, 31), but even in these cases there is no self-confident boasting. When contingency language is used of God, it does not function as a basis on which conclusions may be drawn concerning his ontological limitations: for example, statements about his longsuffering function to underscore the enormity of sin (Num. 14.18), as a foil for human littleness (Jer. 15.15; Ps. 86.15), and as an attribute to be praised (Exod. 34.6). Similarly, God’s pleas for men to repent heighten human wickedness and justify divine wrath (e.g. Jer. 3.22; Ezek. 18.30f.; 33.11; Hos. 14.1), and may even be taken as a measure of his love and hence the evidence that he will act unilaterally on behalf of his people (e.g. Isa. 30.18f.; Hos. 11.7-9).

— Dr. D.A. Carson (PhD, University of Cambridge), Divine Sovereignty & Human Responsibility, Chapter Three, MEN AS RESPONSIBLE. pp. 18-23.

–

If the Old Testament writers everywhere presuppose human responsibility, they not only presuppose divine sovereignty but insistently underscore it, even when the devastations of observable phenomena appear to fly in the face of such belief.

1. God the Creator, Possessor, and Ruler of all Not only did God make everything (Gen. 1f.; Isa. 42.5; Ps. 102.25; Neh. 9.6; etc.), he made it all good (Gen. 1.31). When Israel sang Yahweh’s praise, the remembrance of the fact that he was Maker of heaven and earth afforded great comfort to the people (Ps. 121.2; 124.8). It is not surprising therefore to learn that God is the possessor of heaven and earth (Gen. 14.19,22 (NASB); Ps. 89.11; 1 10 Chr. 29.11f.), or to hear Yahweh insist that all is his (Exod. 19.5; Deut. 10.14; Job 41.3). Hand in hand with such a conception goes the omnipotence of Yahweh. If Yahweh made the heaven and earth, he is the ‘God of all flesh’, and nothing is too hard for him (Jer. 32.17,27; Job 42.2). Since all things are his, no one can give him anything (Job 41.11). All history and nature are at his disposal.

It follows that, if God is sovereign over all the earth, he reigns over all nations (Ps. 47.8f.; 60.6-8; 83.17f.; etc.). This is reasonable enough: all nations belong to him (Ps. 82.8). Indeed, it is when Israel’s fortunes plummet to the darkest depths that her prophets most clearly see Yahweh’s sovereignty over all foreign powers, and take comfort in this truth. The substance of Dan. 2, 4,7f., 10, 11f. is that the Most High rules the kingdom of men (4.25.). To Yahweh, the nations are a mere drop in the bucket, the fine dust of the balance, less than nothing (Isa. 40.15ff.). The pre-exilic prophets in particular teach that Yahweh ‘raises or calls up on the stage of history foreign peoples, Assyrians, Egyptians, Syrians, Philistines, to use them as His instruments… (and) that the foreign peoples, who menaced Israel, were raised up by Yahweh to carry out His plans for the elect people. (Cf. Isa. 7.18; 9.10f.; 10.5f., 26; Jer. 2.6f.; 27.4-8; 31.32; Hos. 2.17; 11.1; 13.4; Amos 2.9f.; 3.1; 9.7; Mic. 6.3ff.; etc.) Examples might easily be multiplied. Yahweh appoints Jehu and Hazael to their tasks; raises Rezin and Pekah against Israel; calls up the king of Assyria; sends the Medes against Babylon, and the Philistines and the Arabians against Judah (1 Kings 19.15-17; 2 Kings 15.37 and Isa. 9.10f.; Isa. 7.17ff. and 10.5; 13.17-19; 2 Chr. 21.16f.). Nor are these foreign powers used only for destruction: Cyrus and the Persians are raised up to restore Israel to the land of her fathers (Isa. 45.1ff.; Ezra 1.1).

Yahweh can well judge all men and nations (Ps. 67.5), for not only is he all-powerful, he is all-knowing. His omniscience is not infrequently associated with the certainty and exhaustive nature of his impending judgment (e.g. Isa. 29.15f.; Jer. 16.16-18; Ezek. 11.2,5; Ps. 139.1ff.; Prov. 5.21; 24.2). When Yahweh has decreed judgment on all nations, who can turn back his hand (Isa. 14.26f.)?